So long and thanks for all the frames

.

We were moving Tritium off egui and into a more powerful UI abstraction to better access OS

primitives, improve rendering and provide extension support.

We were moving over to a declarative UI framework that would allow for us as a team to take Tritium to the

next

level. We were moving to Slint.

Until we didn't.

Some thoughts on why follow.

Rust on the Desktop

A lot of folks are interested in the cross-platform GUI ecosystem in Rust and for good reason.

As the world pumps out an endless stream of bloated Electron applications, those of us who have

to

compete with Microsoft's most performant products don't have the luxury of reading 200mb of binary into RAM

for

each process just to get a pixel on the screen.

No, in 2026, we choose Rust.

If you're in the market for a cross-platform, open source GUI framework where write UI code in Rust without relying on a WebView, your options seem mostly limited to egui, iced and an excellent dual-licensed product called slint.[1]

By the numbers, with 13 million downloads today, egui is a clear winner.

Not only is that around ten times as many as both iced and slint, it even eclipses Tauri -- the

Rust-backed WebView answer to Electron.

Retained versus Immediate Mode GUIs

One quirk of egui is that it is a so-called "immediate mode" GUI framework.

The "immediate mode" GUI was conceived by Casey Muratori in a talk over 20 years ago.

The basic idea of "immediate mode" is this: render frames at your desired rate and on each pass build the UI from scratch, paint it to the buffer and check for interaction.

This is in contrast to "retained mode" GUI frameworks where callbacks and message-passing are used to declare a UI, wait for interaction and asynchronously update the UI state.

The distinction might seem theoretical, but the truth is, immediate mode is super simple.[2]

From the

egui tutorial:

ui.heading("My egui Application");

ui.horizontal(|ui| {

ui.label("Your name: ");

ui.text_edit_singleline(&mut name);

});

ui.add(egui::Slider::new(&mut age, 0..=120).text("age"));

if ui.button("Increment").clicked() {

age += 1;

}

ui.label(format!("Hello '{name}', age {age}"));

ui.image(egui::include_image!("ferris.png"));In egui, gets you:

Compare that with the React tutorial:

export default function MyApp() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Counters that update separately</h1>

<MyButton />

<MyButton />

</div>

);

}

function MyButton() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

function handleClick() {

setCount(count + 1);

}

return (

<button onClick={handleClick}>

Clicked {count} times

</button>

);

}

That's a somewhat unfair comparison because egui packs UI widgets whereas the React example only uses HTML primitives, but the egui example is doing quite a bit more for far less.

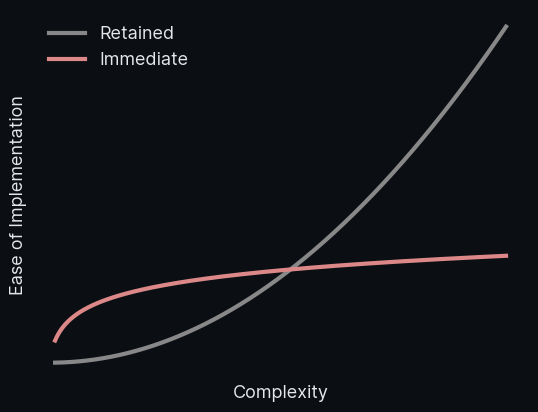

There are two obvious considerations with immediate mode that are somewhat opposed: performance and developer productivity.

Performance

Re-drawing a complicated UI on each frame can become a CPU hog if implemented in a pure "immediate mode" manner.

A single UI element cannot take more than a few microseconds to compute if you need to draw many of them and desire to show 30 to 60 frames per second. This is compounded if you are particular about the UI's appearance because precisely laying out widgets can become non-trivial without reference to the layout of subsequent widgets that will be rendered in the frame.

If you can keep these costs under control and you're already re-drawing frames from scratch at your desired

refresh rate, or you're banging on a development workstation in debug mode this CPU draw is

manageable.

Productivity

Getting started with immediate mode is as simple as creating another global variable and manipulating it during the frame. However, as these variables become interdependent, more logic is needed to determine what to show in a given frame which degrades performance and maintainability.

Optimizing performance increasingly means writing intermediate caching layers, mutating global state, and other complexities and development anti-patterns.

This all results in a productivity tradeoff which looks something like this:

That is, getting a low-to-medium complexity UI in place is far simpler with immediate mode abstractions, but that convenience tails off as the UI's dependecy graph expands.

Dear Imgui sees a lot of action in indy game development circles, for example, because the quick startup time for limited complexity UIs and irrelevant additional CPU usage tip heavily in its favor. But large organizations wrangling complex UIs gravitate towards reactive, declarative frameworks like React that can be more easily collaborated on.

Tritium is an interesting case near the intersection of the two curves.

We only have two developers. And most of the interface in a word processor is the document canvas itself, and the forms surrounding that canvas really just facilitate atomic updates to properties of elements on it. That's doubly true for a legal word processor like Tritium where power users leverage hotkeys over clicking heavily-styled ribbons and buttons.

But development in immediate mode carries some hidden considerations as well.

Logic Creep

First, although it should be straightforward to separate UI and business logic in either framework, fully leveraging immediate mode gains requires developers to nest business logic within UI code.

Let's look at the example egui code again.

ui.heading("My egui Application");

ui.horizontal(|ui| {

ui.label("Your name: ");

ui.text_edit_singleline(&mut name);

});

ui.add(egui::Slider::new(&mut age, 0..=120).text("age"));

if ui.button("Increment").clicked() {

age += 1;

}

ui.label(format!("Hello '{name}', age {age}"));

ui.image(egui::include_image!("ferris.png"));

The example is informative: to update the name appearing in the

salutation at

ui.label(format!("Hello '{name}', age {age}")); it's passed as a mutable string to the

text_edit_singleline method.

That means the salutation needs access to that global value as well.

What starts as a simple accomodation to the framework eventually permeates the application. The entire state is made mutably available to the UI on each pass.

In fact, it's easy to overlook this as a sole developer. A large part of onboarding Nik to the Tritium team and contemplating third-party extensions has been unwinding the business logic from the UI code to make it more modular, maintainable and collaborative.

Power

The second hidden consideration is power draw.

Although there are some tricks and optimizations available, repainting the UI each frame means constant CPU activity while the application is in use.

In a gaming or development environment, the CPU fan is almost always spinning, the computer is likely plugged-in, and the developer is "in the zone" anyway. Tritium users, on the other hand, are less willing to pay the power-draw price of a constant CPU fan when drafting and reviewing legal documents from remote locations on their prior-generation work laptops.

This means that we need to spend a lot of time optimizing the UI code as well as rendering the canvas.

Migrating to Slint solved for both of these issues by providing a declarative and reactive DSL that forced us to separate UI and business logic. It compiles to Rust and includes modern features like live preview. The co-founder of Slint was even willing to accomodate our users leveraging the slint DSL to extend Tritium.

The migration was set to be a clear win for Tritium.[3]

However, ...

Our users expect to open a document from their desktops directly into Tritium.

Setting this up in Windows before Windows 11 only required a little registry work to associate the file type. Today, it requires some COM wrangling to appear in the primary context menu. That's not so fun in 2026, but we're familiar with working in COM and tackling that problem as you read this.

On macOS, the process is theoretically much simpler. We just include some XML in the app's

Info.plist

declaring Tritium capable of opening the file type.

We can also implement a custom protocol to allow networked users to share links to documents across their

network

using the below declaration:

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

...

<key>CFBundleURLTypes</key>

<array>

<dict>

<key>CFBundleURLName</key>

<string>legal.tritium</string>

<key>CFBundleURLSchemes</key>

<array>

<string>tritium</string>

</array>

</dict>

</array>

</dict>

</plist>

This allows users to share a url like tritium://open/?p=WjpcQmxvZ3NcRGVza3RvcC5kb2N4 which is a

base64-encoded path to a copy of this blog post on my network drive.

When another Tritium user on the same network clicks that link, the OS passes the URL to Tritium as a

command-line

argument.

Tritium decodes that argument and launches with roughly the following code:

let mut args: Vec<_> = std::env::args().collect();

if let Some(first) = args.get_mut(1)

&& first.starts_with(config::PROTOCOL_PREFIX_WITH_PARAM)

&& let Ok(path) = document::fs::path_from_tritium_protocol_string(first)

{

return tritium::application::launch(vec![path]);

}Ok. Interesting, but what does this have to do with egui, Slint or the desktop Rust ecosystem generally?

Well, "open with" and this protocol handling works without a hitch on Windows. Windows happily passes the appropriate command line arguments to the application and carries on with life.

On macOS, however, both the protocol and "open with" implementations require a specific handling of the invocation or macOS will hit the user with a notification that the document type isn't supported by the application.

Which brings us back to our desktop UI choice.

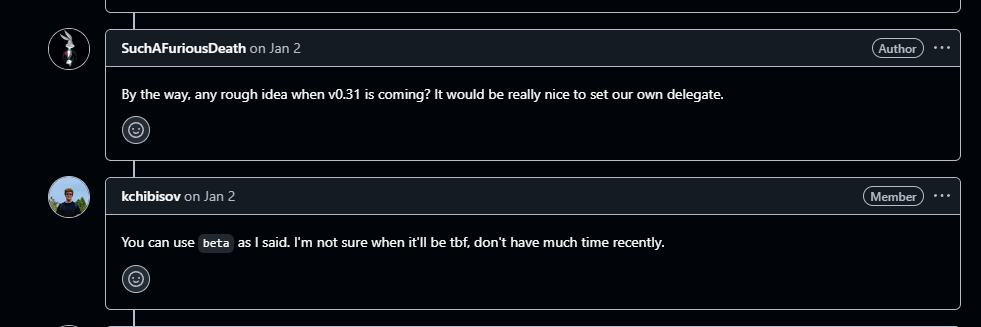

You see, egui relies on the winit for windowing on each platform.

And winit has something like a

bug

on this front making it difficult to interact with the native NSApplication necessary to

receive the

delegation.

The fix comes in winit version 0.31.

And how is that going?

I think we can all relate.[4]

Well, that's just another reason for switching UI frameworks, right?

...

right?

...

The fact is that Slint, like Iced and all other non-WebView-based GUI frameworks, relies on

winit as

its open-source backend[5].

That made me think.

It signalled that even after a migration of the whole code base to a new GUI framework, we'd still be subject to the classic xkcd Jenga tower:

Migrating over to the Slint framework also required completely re-writing the document rendering pipeline. That's rewriting our most important piece of technology to date. We could get there in a couple of months, but we'd likely still be finding bugs for many more after that.

Meanwhile the world is moving on, and fast. How long until even lawyers have abandoned WYSIWYG workflows?

Moving GUI frameworks in the hayday of 2026 might be just the type of unforced error that Joel Spolsky talks about in Things You Should Never Do, Part I. Were we going to be giving up battle-tested code for theoretical organizational gains at just the moment that our industry is taking off?

We pulled the plug after four solid weeks of work. We were 45% of the way to complete.

Instead, we've opted for two solutions.

First, we limit our dependency surface area and patch around the issues we see until we have resources to eliminate the dependency.

In the case of the macOS delegation issue, that patch looks something like this:

const SKIP_DELEGATION_ENV_VAR: &str = "TRITIUM_SKIP_DELEGATION";

...

objc2::declare_class!(

...

unsafe impl NSApplicationDelegate for AppDelegate {

#[method(application:openFiles:)]

fn application_open_files(

&self,

_app: &objc2_app_kit::NSApplication,

filenames: &objc2_foundation::NSArray<objc2_foundation::NSString>,

) {

log::debug!("Launcher: Received openFiles delegation");

let items: Vec<String> = (0..filenames.count())

.map(|i| unsafe { filenames.objectAtIndex(i) }.to_string())

.map(strip_file_protocol)

.collect();

launch_tritium(&items);

std::process::exit(0);

}

}

);

...

fn launch_tritium(args: &[String]) {

let tritium_path = stdx::fs::install_dir().join("tritium");

match std::process::Command::new(&tritium_path)

.args(args)

.env(SKIP_DELEGATION_ENV_VAR, "1")

.spawn()

{

Ok(_) => {

log::debug!("Launcher: Spawned tritium with args: {args:?}");

},

Err(e) => {

log::debug!("Launcher: Failed to spawn tritium at {tritium_path:?}: {e}");

},

}

}

/// Must be called at the start of main(), before any other initialization.

pub fn check_for_delegation() {

if std::env::var(SKIP_DELEGATION_ENV_VAR).is_ok() {

return;

}

...

let Some(mtm) = objc2_foundation::MainThreadMarker::new() else {

return;

};

let app = objc2_app_kit::NSApplication::sharedApplication(mtm);

...

let delegate = AppDelegate::new(mtm);

app.setDelegate(Some(objc2::runtime::ProtocolObject::from_ref(&*delegate)));

...

unsafe {

app.run();

}

// NSApplication.run() corrupts singleton for winit; must spawn fresh child.

log::debug!("Launcher: Spawning child process for clean winit startup");

launch_tritium(&[]);

std::process::exit(0);

}

We solve by checking for the delegation in main before winit gets

involved,

then forking into either a clean launch or a launch with the command line arguments expected by Tritium.

Second, we embrace the need for separation of concerns and (over time) refactor our egui code

into a

thin client interacting with an off-thread Server which coordinates the global state.

In short, we build.

-

We ignore for these purposes Zed's GPUI which the Zed team has transparently, and understandably

abandoned as an

open source endeavour.

Floemis another good candidate that the Tritium team did not consider but suffers from the same issue discussed herein. - No doubt this simplicity has played a significant role in

egui's adoption on the desktop. - One positive side effect of optimizing for immediate mode is that developers must focus on the rendering time of each frame and heavy operations won't come as a surprise out of some obscure corner of the UI.

- Developer burnout in OSS is a separate and additional question to the economic viability of open source software, and particularly dual license business models in the presence of LLMs that are happy to regurgitate useful code without an understanding of licensing issues.

- Slint does integrate nicely with the Qt backend which might be an attractive option for those willing to include Qt as a dependency under either an AGPL or commercial license.